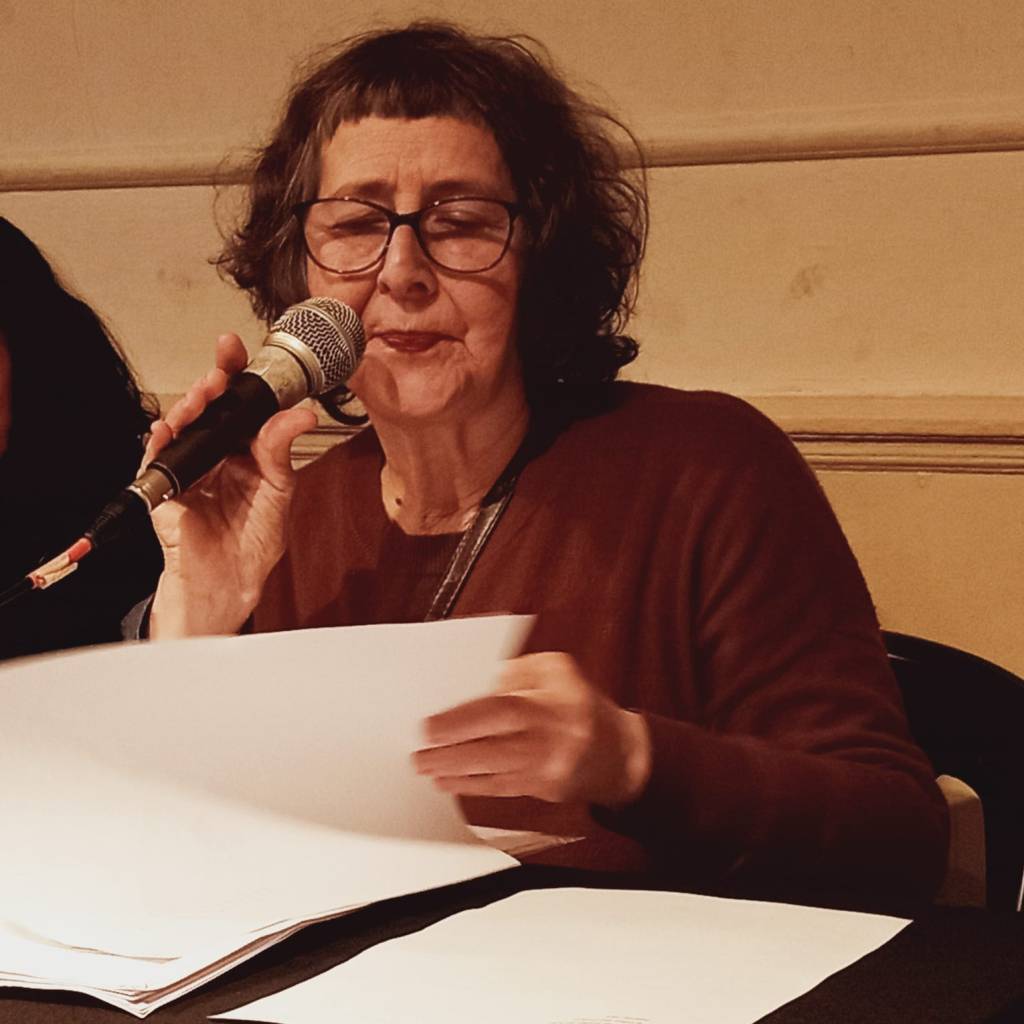

Jonio González nació en Buenos Aires en 1954 y vive en Barcelona desde 1983. En 1981 fundó, con Javier Cófreces, la revista de poesía La Danza del Ratón.

Es autor, entre otros títulos, de los poemarios El oro de la república (1982); Muro de máscaras (1987); Cecil (1991); Últimos poemas de Eunice Cohen (1999); El puente (2001, 2003); Ganar el desierto (2009); La invención de los venenos (2015), Historia del visitante (2019) y Esbozos y representaciones (2022). Ha sido incluido en diversas antologías, entre ellas Una antología de la poesía argentina (Santiago de Chile, 2008); Doscientos años de poesía argentina (Buenos Aires, 2010); Antología de poesía argentina de hoy (Barcelona, 2010); Poésie récente d’Argentine: une anthologie possible (París, 2013) y La doble sombra: poesía argentina contemporánea (Madrid, 2014). Como traductor de poesía, sus últimas publicaciones incluyen la antología en dos volúmenes Poetas norteamericanos en dos siglos (2020) y Esperando mi vida, de Linda Pastan (conjuntamente con Rosa Lentini, 2021). ha colaborado traduciendo a varios poetas en In nomine Auschwitz.Antología de la poesía del Holocausto , de Carlos Morales del Coso (2022).

Otros artículos de este autor

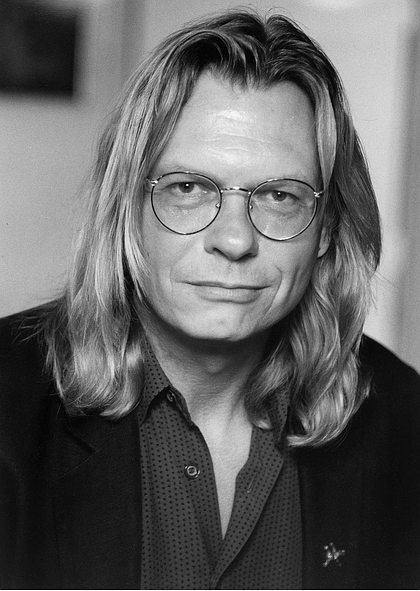

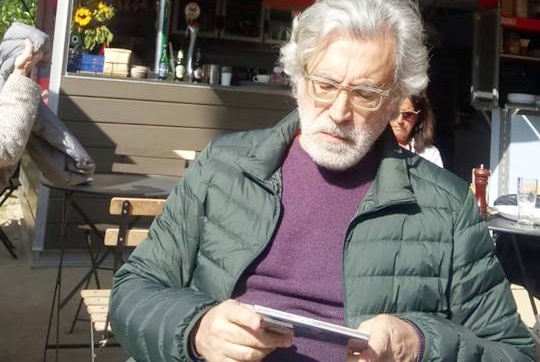

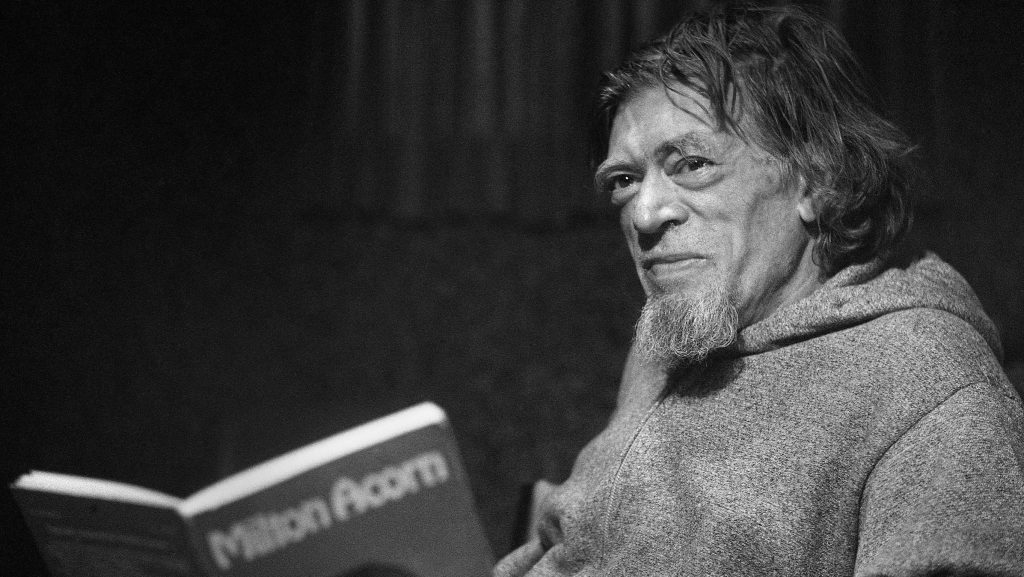

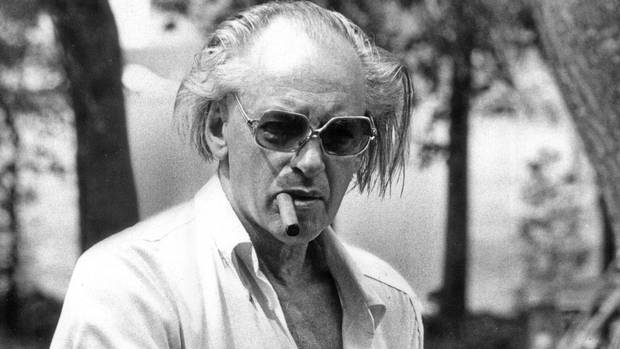

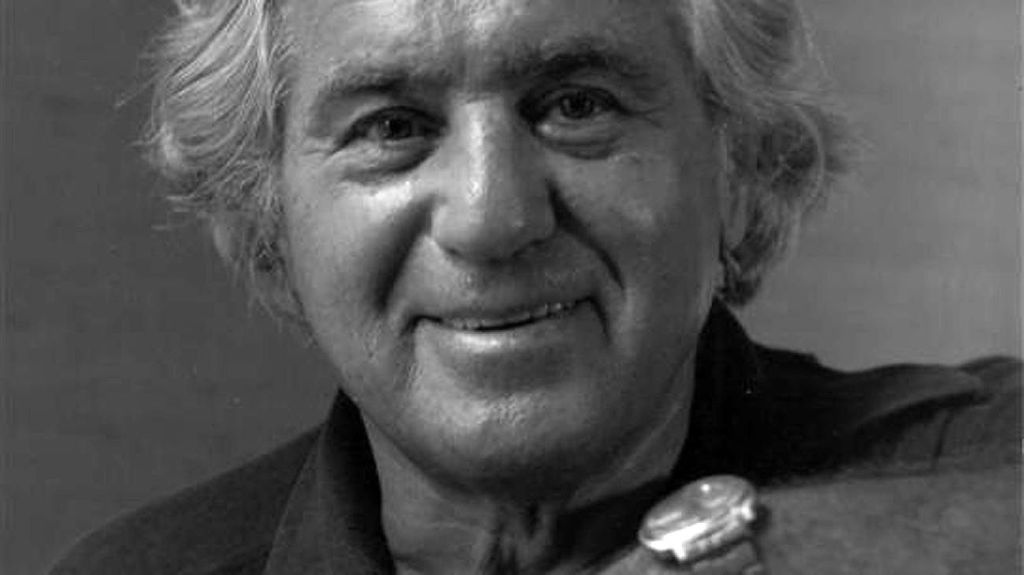

THOMAS LUX

THOMAS LUX nació Northampton, Massachusetts, en 1946, en el seno de una familia de clase trabajadora (vivía en una granja, su padre era lechero). Estudió en el Emerson College, donde fue poeta residente entre 1971 y 1975, y en la Universidad de Iowa. Durante casi treinta años fue profesor de escritura creativa en el Sarah Lawrence College. Publicó catorce libros de poesía, entre ellos Memory’s handgrenade (1972), The Glassblower’s Breath (1976); Sunday (1979); The Drowned River (1990); The Blind Swimmer: Selected Early Poems, 1970–1975 (1996); New and Selected Poems, 1975–1995 (1997); The Street of Clocks (2001); Child Made of Sand (2012) y To the Left of Time (2016). Su poesía, influida al principio por el neosurrealismo de los años setenta en general y James Tate y Bill Knott en particular, evolucionó hacia, en palabras de Richard Damashek, una complejidad que «refleja un mundo tan insano como inhóspito». Lux murió en Atlanta, Georgia, en 2017.

EL LECHERO Y SU HIJO

Durante un año recogió

las botellas de leche, las rajadas,

rotas, o con la etiqueta azul

con el dibujo de una granja

desteñido. En invierno

cargaban las cajas en un trineo

y las arrastraban hasta el basural

que entonces era precioso: una sábana blanca

tendida, como una broma, sobre

la cara de alguien que dormía.

Mientras arrojaban las botellas

el hijo hacía travesuras

y el lechero se las festejaba: lanzaba

una botella a gran altura

y la hacía añicos al vuelo

con otra. Mil asombrados

trozos de vidrio

caían... Otra vez

y otra, y maldito

si ese lechero,

ese alegre lanzador

en el borde del basural (mientras los voladores

desechos salpicaban de nieve

sus sombreros)

THE MILKMAN AND HIS SON

For a year he’d collect

the milk bottles—those cracked,

chipped, or with the label’s blue

scene of a farm

fading. In winter

they’d load the boxes on a sled

and drag them to the dump

which was lovely then: a white sheet

drawn up, like a joke, over

the face of a sleeper.

As they lob the bottles in

the son begs a trick

and the milkman obliges: tossing

one bottle in a high arc

he shatters it in midair

with another. One thousand

astonished splints of glass

falling…Again

and again, and damned

if that milkman,

that easy slinger

on the dump’s edge (as the drifted

junk tips its hats

of snow) damned if he didn’t

hit almost half! Not bad.

Along with gentleness,

and the sane bewilderment

of understanding nothing cruel,

it was a thing he did best.

TARÁNTULAS EN EL SALVAVIDAS

Por algún motivo semitropical

cuando llueve

implacablemente caen

en las piscinas estos por lo demás

brillantes y terroríficos

arácnidos. Pueden nadar

un poco, no por mucho tiempo,

y no pueden subir por la escalera para escapar.

Por lo general se ahogan, pero

si quieres su favor,

si crees que existe la justicia,

una recompensa por no querer

la muerte de desagradables

y aun peligrosas (anguilas, serpientes nariz de cerdo,

ratas) criaturas, si

crees estas cosas, entonces

tendrías que dejar un salvavidas

o dos en tu piscina por la noche.

Y por la mañana

arrastrarías fuera

las acurrucadas, peludas supervivientes

y las acompañarías

de nuevo al matorral y, ¿sabes?,

te asegurarías de que al menos las que se han salvado,

como individuos, no aparecerán

de nuevo un día

en tu sombrero, un cajón

o el enmarañado inframundo

de tus calcetines, y que incluso—

cuando tu confianza en la justicia

se une a tu confianza en los sueños—

pueden comunicar a las otras

mediante un lenguaje de signos

cuatro veces más ingenioso

y complejo que el del hombre

que eres bueno,

que las amas

que las salvarías de nuevo.

TARANTULAS ON THE LIFEBUOY

For some semitropical reason

when the rains fall

relentlessly they fall

into swimming pools, these otherwise

bright and scary

arachnids. They can swim

a little, but not for long

and they can’t climb the ladder out.

They usually drown—but

if you want their favor,

if you believe there is justice,

a reward for not loving

the death of ugly

and even dangerous (the eel, hog snake,

rats) creatures, if

you believe these things, then

you would leave a lifebuoy

or two in your swimming pool at night.

And in the morning

you would haul ashore

the huddled, hairy survivors

and escort them

back to the bush, and know,

be assured that at least these saved,

as individuals, would not turn up

again someday

in your hat, drawer,

or the tangled underworld

of your socks, and that even—

when your belief in justice

merges with your belief in dreams—

they may tell the others

in a sign language

four times as subtle

and complicated as man’s

that you are good,

that you love them,

that you would save them again.

EN EL DORMITORIO DE ENCIMA DE LA SALA DE EMBALSAMAMIENTO

un hombre con camiseta blanca y medias blancas sentado

en el borde de la cama. Es mi vecino,

el de la funeraria del barrio.

Su esposa está acostada a su lado, leyendo un libro,

la sábana le cubre los pechos.

De lo contrario, mirarla sería de mala educación.

O para mirar debería esperar a que se vistiesen.

Desde mi ventana forman una especie de X.

A ella la he visto dar de comer a los pájaros,

pero no mucho para que no se queden

demasiado y dejen sus huellas de cal

en el escritorio y le hagan perder el tiempo

lavándolo.

IN THE BEDROOM ABOVE THE EMBALMING ROOM

a man sits on the bed’s edge in a white T-shirt,

white socks. He is my neighbour,

the local undertaker.

His wife lies behind him, reading a book,

the sheet drawn up above her breasts.

Otherwise, it would be impolite to look.

Or to look I’d wait until they dressed.

From my window they make a kind of X.

I’ve seen her feed the birds,

but not so much they stay

too long and leave their lime

to stain her deck and waste her time

in washing it away.

LADRILLOS QUE SE HUNDEN EN AGUAS PROFUNDAS

¿A qué profundidad desaparece su opaco color anaranjado?

Remé hasta donde sé que el agua es profunda,

y en mi bote: un cargamento

de ladrillos, cincuenta apilados

en la popa, así de simple.

En el fondo de este embalse

había un pueblo. Dos pueblos, en realidad.

A su gente se le pagó una suma justa

para que se fuera, pero sin hacer preguntas: tenían que trasladarse.

Echo el ancla cuarenta pies por encima

de lo que una vez fue un prado.

Primero agarro un ladrillo de babor

y lo sujeto por la esquina superior derecha

y meto su esquina inferior izquierda en el agua

antes de dejar que resbale entre mis dedos.

El siguiente lo agarro de estribor,

pero ha caído de babor, y así sucesivamente.

La mano izquierda es la que hace el trabajo.

Es visto y no visto. Se hunden hasta detenerse

en lo que ahora es una tierra anegada y sin hierba.

¿Por qué quiero dejar unas cuantas

piedras trangulares artificiales

en el fondo de este cuerpo de agua sin huesos?

(el cementerio fue trasladado).

¿Quién no ha amado, en la oscuridad,

el borroso, fuerte, anaranjado resplandor

de los ladrillos?

BRICKS SINKING IN DEEP WATER

At what depth does their dull orange disappear?

I rowed out to where I know the water’s deep,

and in my rowboat: a cargo

of bricks, fifty balanced

across the stern, just so.

At the bottom of this reservoir

was a town. Two towns, in truth.

Its people were paid an honest price

to leave, but no question: they had to move.

I anchor my boat forty feet above

what was once a pasture.

I take a brick from port first

and hold it by its upper right corner

and dip its lower left corner into the water

before I let it slip my fingers.

The next one I take from starboard,

but drop from port, and so forth and on.

It’s the sinestra hand that does the work.

I never counted two seconds before one was gone

from touch, and sound, and sight. They sink until they stop

on now drowned and grassless land.

Why do I want to leave a small scattering

of man-made triangular stones

at the bottom of this no-bones

(the cemetery relocated)

body of water? In darkness, who does not love

the faint, hard, orange glow

of building bricks?

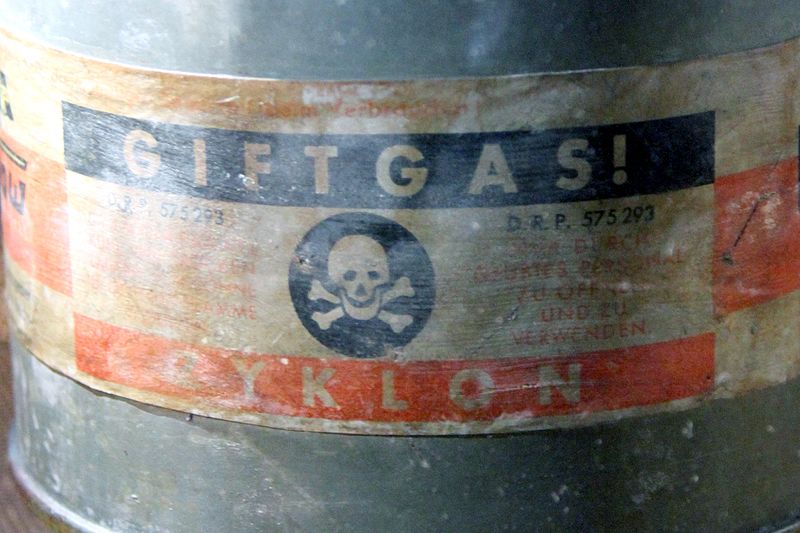

VÍCTIMAS DE LA PLAGA ARROJADAS POR ENCIMA DE LOS MUROS DE LA CIUDAD SITIADA

Primera guerra

biológica.

La muerte

así lanzada semeja ruedas

en el cielo.

Mira: ahí va

Larry el Zapatero, descalzo, por encima de la pared,

y Mary la Salchichera, mira cómo vuela,

y los mellizos Sombrereros, los dos a la vez, sobrevolando

el parapeto, el codo del pequeño Tommy doblado

como si saludara,

y su hermana, Mathilda, detrás de él,

con los brazos extendidos, en el aire,

igual que hizo

en la tierra.

PLAGUE VICTIMS CATAPULTED OVER WALLS INTO BESIEGED CITY

Early germ

warfare.

The dead

hurled this way look like wheels

in the sky.

Look: there goes

Larry the Shoemaker, barefoot, over the wall,

and Mary Sausage Stuffer, see how she flies,

and the Hatter twins, both at once, soar

over the parapet, little Tommy's elbow bent

as if in a salute,

and his sister, Mathilde, she follows him,

arms outstretched, through the air,

just as she did

on earth.

También te puede interesar

La fotografía de portada ha sido extraída de «The Paris Rewiew» de Dan Piepenbring

Deja un comentario